Imagine you could restore health and

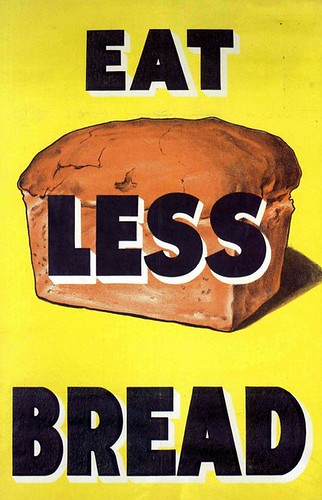

lose weight by eating fats and protein and consuming fewer carbohydrates, i.e.

sugar and grains. This was standard medical advice up until the late 1970s.

Then the advice changed to “eat more grains and limit saturated fats”. The new

“healthy eating” advice was never subjected to rigorous testing before the old

advice, which had served society well, was ignominiously dumped. Are we, as a

nation, now fitter, better nourished, and less disease prone as a result?

The Kiwi ANZACs, widely considered to be the fittest troops in the Allied armies in two world wars, were raised in a nation where per capita weekly butter consumption was 415 grams. It is now 112 grams, which is half of the reduced 1940s wartime ration. The consumption of fat from red meat has also decreased as drastically. We eat fewer eggs and drink less full-fat milk.

There is a fallacy that stems initially from the Western intellectual's sense of cultural inadequacy and guilt, and the assumption that Eastern cultures must somehow be purer and wiser. One of the features of Eastern religious culture identified early on by aficionados like Schopenhauer – because the things that are unusual in a culture attract attention first - was vegetarianism. The reality of Buddhist and Hindu society, like all successful human society, didn't involve denial of animal foods (the Dalai Lama eats meat, observant Hindus cook with butter fat), but the ideal, already present in Western ascetic tradition and not associated there with robust physical or mental health, had a persistent appeal, which found expression in the early temperance, vegetarian and vegan movements.

The Kiwi ANZACs, widely considered to be the fittest troops in the Allied armies in two world wars, were raised in a nation where per capita weekly butter consumption was 415 grams. It is now 112 grams, which is half of the reduced 1940s wartime ration. The consumption of fat from red meat has also decreased as drastically. We eat fewer eggs and drink less full-fat milk.

There is a fallacy that stems initially from the Western intellectual's sense of cultural inadequacy and guilt, and the assumption that Eastern cultures must somehow be purer and wiser. One of the features of Eastern religious culture identified early on by aficionados like Schopenhauer – because the things that are unusual in a culture attract attention first - was vegetarianism. The reality of Buddhist and Hindu society, like all successful human society, didn't involve denial of animal foods (the Dalai Lama eats meat, observant Hindus cook with butter fat), but the ideal, already present in Western ascetic tradition and not associated there with robust physical or mental health, had a persistent appeal, which found expression in the early temperance, vegetarian and vegan movements.

We then come to a point in history -

the 60's - 70's counterculture - where the idea took hold more widely, through

music and other popular media, that vegetarianism (and other aspects of Eastern

religious thought) represented the higher path, while the habits of the older

generation were anathematized; including

church-going, smoking, drinking, meat eating.

Various influential people exposed to

this assumption in their formative years unconsciously accepted it as

factual. The same bias can be seen to persist today when veganism,

despite its risks, is accepted as normal by government dieticians as

somehow being worth nurturing as the expression of a noble and virtuous

impulse; whereas the Atkins type of high fat, low carb diet is not to be

encouraged, despite the scientific evidence in its favour and common-sense

assessments of its nutritive value, because it is seen as self-indulgent. Deep

psychological forces decide the values different foods are given, and mystical,

revolutionary, and puritanical impulses as well as economic and social pressures

distort the collection, interpretation and publication of data.

Scientific research has been

misinterpreted to reflect an existing prejudice, and this has suited the food

manufacturing industry, with novel oil, grain, and soy products to find markets

for. A perfect storm of error has formed around the question of fat, because of

the earlier invention of the cholesterol test, which seemed to support the new

belief, and which lent it a spurious validity. The animal fat in our diets has

been the ultimate casualty.

Most people cannot stay vegetarian

for good reasons, and many backslide, but not all the way, only to the

"vegan meat" chicken, to lean meats, low fat dairy and so

on. It's as if by avoiding what one thinks is "saturated" fat

one can avoid the sinful aspects of consuming flesh. The very word “saturated”,

a technical description of chemical bonds, conveys unintended connotations of

excess.

Yet highly saturated fats like beef

dripping and coconut oil have a remarkable ability to protect the liver from

the toxicity of alcohol or other drugs. Polyunsaturated fats have the opposite

effect. That seems like something that should be more widely known, instead of

confined to those medical journals that specialize in alcoholism. It should

also be more widely known that people who eat the most dairy fat have half the

diabetes incidence of the people who eat the least, or that, all over the

world, those who attempt suicide tend to have significantly lower cholesterol

levels than those who do not. And so on.

It was studying the life cycle of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that eventually forced me to question my received beliefs about fat, carbohydrate, and cholesterol:

- HCV depresses and monopolises

cholesterol production; cholesterol in the diet counteracts this.

- HCV uses VLDL to exit infected cells; starches and sugars increase VLDL production.

- HCV uses VLDL to exit infected cells; starches and sugars increase VLDL production.

- Saturated fats in a

low-carbohydrate diet (and omega 3 oils from fatty fish) decrease it.

- HCV infects new cells through the LDL receptor; polyunsaturated vegetable oils increase the number of LDL receptors.

- HCV infects new cells through the LDL receptor; polyunsaturated vegetable oils increase the number of LDL receptors.

- If you have Hepatitis C, your prospects improve with higher LDL levels (a sign

of fewer LDL receptors).

- HCV depresses immunity by sequestering zinc and selenium; these minerals are most easily absorbed from fatty foods like meat, seafood and Brazil nuts; their absorption is inhibited by most grains and legumes.

- HCV depresses immunity by sequestering zinc and selenium; these minerals are most easily absorbed from fatty foods like meat, seafood and Brazil nuts; their absorption is inhibited by most grains and legumes.

- The antioxidants from leafy vegetables, fruits and berries are

valuable, but they are no substitute for animal fats and carbohydrate

restriction when it comes to clearing a fatty liver, reducing viral

replication, or preventing disease progression.

In the case of at least two diseases,

the not uncommon ones of hepatitis C and alcoholism, the two main causes of

cirrhosis and primary liver cancer in this country, current “healthy

eating” advice can only be increasing harms. Fast food is not so different;

fries are vegetable starch cooked in polyunsaturated vegetable seed oil,

supposed to be a healthy alternative to animal fat because it “lowers

cholesterol”.

Nutritional epidemiologists write

papers about the French paradox, whereby the French, who have largely preserved

their traditional diets, diets which happen to be rich in animal fats, have

relatively low levels of heart disease, and also low rates of liver cirrhosis

relative to the amount of alcohol consumed in France. In the case of the

Israeli paradox, this health-conscious population has adopted modern ideas

about healthy eating, especially that of reducing saturated fat by substituting

polyunsaturated vegetable oils for animal fats, and now has relatively high

rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer. That these results

are considered paradoxical because they contradict unproven assertions should

be an embarrassment to science.

(paradox, n.

Statement contrary to received opinion; statement that, whether true or not,

seems absurd at first hearing; person or thing conflicting with preconceived

notions of the reasonable or possible.)

Knowing all this, and also

considering what our hardier ancestors might once have eaten, and what they

could not have eaten, takes us back to the days before the cholesterol craze,

before the food processing industry cashed in on vegetarian values,

before dieticians became anserine media hacks. Sugars, grains and

legumes, and seed oils, as well as the vast array of novel foods made with

them, are worth limiting or avoiding. To avoid obesity, to treat diabetes and

degenerative diseases, restrict carbohydrates. Fat is your friend, cholesterol

is an essential part of your body, and animal foods are the most nutritious

foods, with vegetable foods as valuable supplements.

Inquiry into diet has always been

part of the philosophical tradition, for example in the writings of Lucretius,

Montaigne, Lichtenberg, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, because nutrition science

is, or should be, concerned with the same questions as philosophy; how do we

know what we know?, and, how should we live our lives? The well-designed

experiment that can settle a question will always be a commodity that is

valuable precisely because it is rare. Since the existence of the deficiency

diseases and the harmful effects of smoking and excessive alcohol consumption

were proven many years ago it has become unusual for diet and lifestyle studies

to generate results that justify sweeping statements or universal

recommendations. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution,

and it is only in the light of human evolution that we can hope to make sense

of the human diet and its link to disease.

Originally published in the Café Reader, a fine literary magazine produced by the New Zealand-based company Phantom Billstickers.